Osterloh was traveling north on Georgia 400 when he was struck by another vehicle. Osterloh’s vehicle skidded off the roadway and stopped at the tree line. Osterloh lost consciousness during the accident. He awoke with his head outside the passenger window. He told deputies that he was on his way to Chicago when his car was struck three times. He informed Forsyth County deputies of his name, a rod in his leg, hit his head in the accident, and was not on any medication. He had a significant limp and indicated that his leg was injured.

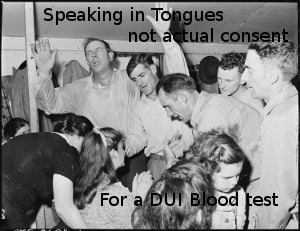

After several minutes of speaking with the deputies. Osterloh started screaming and ran toward the road. He then became uncooperative refused to stand where told and spread his arms wide open. He was then pinned to the ground and handcuffed by four deputies. Once on the ground, Osterloh began “speaking in tongues,” an unknown language, or yelling in gibberish. The speaking in tongues lasted for several minutes. Osterloh would not calm down. EMTs responded and determined that Osterloh was breathing normally but had dilated pupils. Osterloh was then arrested for DUI and read Georgia DUI implied consent rights for a blood test. He interrupted the deputy and yelled, I ain’t going to trial dumbass. What you read that for?” He then responded yes that he would submit to a blood test.

Osterloh was not threatened nor did the deputies brandish their guns. Two deputies were holding Osterloh on the ground and he was heaving and vomiting a purple liquid. Osterloh remained on the ground speaking in tongues for 15 minutes until an ambulance arrived to transport him to the hospital for a DUI blood test. Osterloh was combative at the hospital and had to be immobilized during the blood draw. He spent three days in the intensive care unit and had to be placed into a medically induced coma. He had head injuries, vomited blood, had blood in his urine, and suffered respiratory failure. Osterloh testified that he had no recollection of the immediate aftermath of the incident.

The trial court found that there was no actual consent to a blood test as Osterloh was injured and incapable of making any rational decision. The Trial Court further held that Osterloh was lying flat on the ground, speaking in tongues and either vomiting or choking during Implied Consent.

A DUI defendant’s right to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures applies to DUI blood tests. Williams v. State, 296 Ga. 817, 819 (771 SE2d 373) (2015). Blood extraction is a search under the Georgia Constitution. There are two searches. There are searches with a warrant and those without a warrant. Id. Warrantless searches are presumed to be invalid and the State must prove otherwise. Id. In the context of a DUI, blood draws a valid consent to search eliminate the need for probable cause or a search warrant. Id. To obtain a blood sample, the State must comply with Georgia’s Implied Consent statute. However, In Williams v. State, the Georgia Supreme Court held that mere compliance with statutory implied consent requirements does not equal actual consent under the 4th Amendment. Id. Actual consent must be determined about the voluntariness of the consent under the totality of the circumstances on a case by case basis. Id. Under Georgia Law, voluntariness must be an exercise of free will and not a mere acquiescence or submission to express or implied authority. State v. Bowman, 337 Ga. App. 313, 787 SE2d 284 (2016). Under, the above facts, the Coua rt of Appeals found that there was not an absence of evidence demanding a finding of actual consent under the circumstances. On the contrary, suffering a serious injury, vomiting blood, dilated pupils, and continued speaking in tongues, all pointed to a lack of actual consent.

The Court of Appeals also pointed out that nothing prevented the state from seeking a warrant for the Defendant’s blood rather than resting on his consent given his questionable medical and mental condition.

-Author: George C Creal Jr

-Image: Public Domain