Georgia Implied Consent rights codified at OCGA 40-5-67.1 provide:

“Georgia law requires you to submit to state-administered chemical tests of your blood, breath, urine, or other bodily substances for the purpose of determining if you are under the influence of alcohol or drugs. If you refuse this testing, your Georgia driver’s license or privilege to drive on the highways of this state will be suspended for a minimum period of one year. Your refusal to submit to the required testing may be offered into evidence against you at trial. If you submit to testing and the results indicate an alcohol concentration of 0.08 grams or more, your Georgia driver’s license or privilege to drive on the highways of this state may be suspended for a minimum period of one year. After first submitting to the required state tests, you are entitled to additional chemical tests of your blood, breath, urine, or other bodily substances at your own expense and from qualified personnel of your choosing. Will you submit to the state-administered chemical tests of your ( designate which tests ) under the implied consent law?”

First, Guiterrez is completely distinguishable or it should be reversed. The Guitierrez Court found that Implied Consent was not misleadingly deceptive, coercive, deceptive, and misstated the true and legitimate consequences of both the refusal and submitting to the test because the Officer did not ever submit the DPS now DDS Form 1205. This is a legitimate permissible range of sanctions because the Officer is informing Defendant of the permissible range of sanctions at that moment he read implied consent. If the Officer chooses not to send the DDS Form 1205 later that does not change the facts at the time of issuance of the Form 1205. However, Oyeniyi is challenging not when the officer does not submit Form 1205 but when he does submit Form 1205. The Guiterrez Court’s reliance on Whittington v. State, 184 Ga. App. 282, 283-284, 361 SE2d 871 (1986) does not apply to this situation as “permissible range of sanctions” referenced the Officer’s warning that Whittington would lose his license for “6 to 12 months” under then OCGA 40-5-55 which would have been 6 months with no fatalities but could increase to 12 months if a fatality later occurred from injuries resulting from the accident at issue. In Oyeniyi, the fact and consequences were set at the time of the implied consent rights and would not change later.

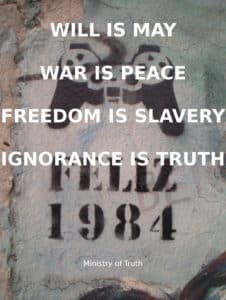

Will means Will. “Will suspend” does not mean mayor a potential range of sanctions or may suspend if certain events occur in the future. The most direct is the scenario contemplated by O.C.G.A. §40-5-67.1(g)(4), which requires the Department of Drivers’ Services to terminate and delete the suspension in the event of an acquittal or disposition other than conviction or plea of nolo contendere to DUI. Additionally, O.C.G.A. §40-5-67.1(g)(3) contemplates the scenario where an Office of State Administrative Hearings officer shall forward a decision to rescind any suspension to the Department of Drivers’ Services. Finally, O.C.G.A. §40-5-67.1(h) guarantees the right to appeal any decision to suspend a driving privilege, setting up yet another alternative outcome, with a reversal of the decision in a higher court. In these ways, any suspension is highly dependent on other conditions, making the use of the word “WILL” an inaccurate statement of the law. It cannot be argued that the State uses the unequivocal word “WILL” only because the suspension occurs by operation of law, and the other scenarios described above are simply results of hearings and decisions outside the scope of the legally imposed one-year suspension. This argument is meritless because of the juxtaposition of the word “MAY” in the second portion of the Implied Consent notice describing the penalty for submitting to the test with results indicating a blood alcohol concentration of 0.08 grams or more. By employing the word “MAY” at this juncture in the Implied Consent notice, the State acknowledges the conditional nature of any suspension, and complies with United States Constitutional law. See Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535 (1971) (holding that automatic suspensions of driving privileges without a hearing are unconstitutional). O.C.G.A. §40-5-67.1(c) requires, in no uncertain terms, that where a driver submits to a chemical test indicating a proscribed blood alcohol concentration, that “the department shall suspend the person’s driver’s license, permit, or nonresident operating privilege…” (Emphasis supplied). This use of the word “MAY” indicates the State’s acknowledgment that conditions exist wherein a suspension “MAY” be lifted before the expiration of one year, such as the above-enumerated scenarios of O.C.G.A. §40-5-67.1(g)(3-4) and (h). Thus, any argument that the word “WILL” is used accurately as only describing the suspension by operation of law fails to hold water in juxtaposition with the State’s obvious acknowledgment, when it thereafter uses the word “MAY,” that conditions do exist which result in a different outcome than suspension. This shift to the use of the word “MAY” is much more reasonably explained by the State’s desire to induce its desired result—that of a test result to use against the defendant in the ensuing criminal prosecution—than it is by arguing that the State’s double-standard in this regard is an accurate statement of the law.

Second, the Singleterry case says nothing of the sort. Singleterry merely holds that an arresting officers failure to file a DPS now DDS Form 1205 does not render the implied consent misleading and coercive as the Implied Consent rights do not promise the immediate filing of the 1205 form and the statute contemplates when the officers fail to file the 1205 form in OCGA 40-5-67.1(f).

Third, in Sauls v. State, 293 Ga. 165, 744 SE2d 735 (2013), the issue was not informing a driver that a refusal could be used against him at trial. The Supreme Court found that failure to tell a driver that a refusal could be used against him at his criminal trial made the implied consent rights substantially inaccurate and reversed the Court of Appeals’ opinion that the Implied Consent Rights were substantially accurate. The Sauls court held that “drivers should be made aware of the …consequence of the refusal of testing.” Telling a driver that his license will be suspended if he refuses versus may be suspended if he blows over the legal limit is little more than a thinly veiled attempt to coerce the driver into blowing. In reality, if the driver refuses or blows over the legal limit his license may be suspended for a year. This is too important of a consequence to allow inaccuracies to give false weight.

The Oyeniyi Court also found that due process rights are not implicated when the statutory implied consent does not inform the driver of all possible outcomes of a refusal citing Sauls, supra, (Which only held that a violation of due process is not implicated when the statutory implied consent notice does not inform the driver that test results could be used against the driver at trial and subsequently found the failure to inform the driver of such consequence substantially inaccurate and reversible.). The only good news from this opinion is that it is pre-Williams and only deals with the issue of “misleadingly deceptive”/”Substantially Inaccurate” DUI Implied Consent rights and does not rise to effect any Constitutional arguments or issues that may be implicated by the Williams decision. Click here to read more on Williams.

-Author: George C. Creal, Jr.