The Protection of the 4th Amendment

The 4th Amendment to the United States Constitution provides:

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects,[a] against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

Similarly, Article 1, Section 1 of the Georgia Constitution provides in Paragraph XIII:

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures shall not be violated; and no warrant shall issue except upon probable cause supported by oath or affirmation particularly describing the place or places to be searched and the persons or things to be seized.”

But what is an unreasonable search and seizure? Courts have been debating this question for years, and the debate rages on in city and state courts across the country.

While there are no bright line answers to this question, it is important to know how courts attempt to define where your rights begin and where the Government’s end. The following section focuses on the ability of the government to search your home without consent –or with consent obtained through intimidation or coercion in the absence of exigent circumstances – as delineated by Georgia courts and SCOTUS. Remember that each set of facts is unique, and a court will look to the totality of the circumstances of your particular case to decide whether your Fourth Amendment rights were violated. Our goal is to provide you with a general understanding of your rights as you encounter police officers at your home, especially through uninvited knock and talks.

The Knock and Talk

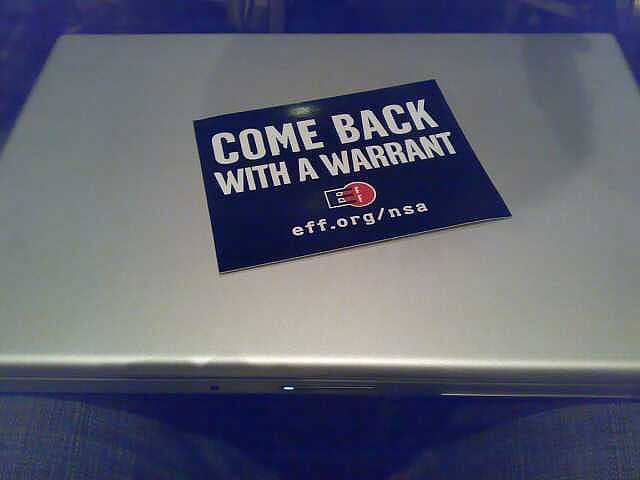

In police parlance, a “knock and talk” is an investigative technique in which one or more police officers approach a private residence and knock on the door. The police then request consent from the owner to search the residence. The knock and talk is often performed police suspect criminal activity but there is insufficient evidence to obtain a search warrant, the police do not believe that they can get a warrant or the police are too lazy to take the time to apply for a warrant. It is commonly used to circumvent the protections of the 4th Amendment.

The State bears the burden of proving that both the search and seizure of evidence were lawful. OCGA § 17-5-30(b). To justify a warrantless search through consent, the State must prove the consent was voluntary under the totality of the circumstances. Pledger v. State, 257 Ga.App. 794, 800, 572 S.E.2d 348 (2002), citing Raulerson v. State, 268 Ga. 623, 625(2)(a), 491 S.E.2d 791 (1997), and Schneckloth v. Bustamonte, 412 U.S. 218, 229, 93 S.Ct. 2041, 36 L.Ed.2d 854 (1973). “[I]n order to eliminate any taint from an involuntary [search,] seizure or arrest, there must be proof both that the consent was voluntary and that it was not the product of [an] illegal detention.” Pledger, supra. Whether consent is the product of free will or the preceding illegality must be answered on the facts of each case; no single fact is dispositive. Brown v. Illinois, 422 U.S. 590, 603, 95 S.Ct. 2254, 45 L.Ed.2d 416 (1975).

In Pledger v. State, supra, police went to the accused home after receiving a tip from an informant that alleged that there was marijuana in the home. Because the tipster was considered unreliable, the police opted to perform a “knock and talk” to attempt to obtain consent voluntarily from the suspect, knowing they would not be able to obtain a warrant. When they went to Pledger’s home, she was not home but a young visitor answered the door and they smelled marijuana. The police took the visitors of the home into custody while they waited inside and obtained a warrant. When Pledger arrived home, she was met by four officers inside her home and she consented to a search. The Court held that the search did not occur with valid consent because it was obtained as a result of illegal entry of the home.

Whether consent is voluntary is a crucial determination by the trial court. In Pollard v. State, 265 Ga. App. 749 (2004), the Georgia Court of Appeals laid out the factors to be considered to determine whether consent is voluntary under a totality of the circumstances analysis:

1) the age of the accused,

2) his education,

3) his intelligence,

4) the length of detention,

5) whether the accused was advised of his constitutional rights,

6) the prolonged nature of questioning,

7) the use of physical punishment, and

8) the psychological impact of all these factors on the accused.

A mere knock by the police on someone’s door and request to enter the premises usually constitutes a first-tier encounter. A second-tier encounter occurs if a reasonable person would have felt compelled to open the door and let the police enter under a totality of the circumstances This is important because if the knock becomes a second-tier encounter without articulable suspicion, any subsequent consent would be tainted. Black v. State, 281 Ga.App. 40, 44(1), 635 S.E.2d 568 (2006).

For more information on First and Second Tier Encounters click here.

Because this is only a first tier, consensual encounter, you are under no obligation to speak with the police officer. Similarly, you are under no obligation to let the officer search your vehicle. However, if you feel compelled to speak with the officer based on his conduct and mannerisms, or the content and tone of his questioning, what may have begun as a consensual encounter is now an investigatory stop.

Warrantless Searches

It is well established “that searches conducted outside the judicial process [or warrantless searches], without prior approval by judge or magistrate, are per se unreasonable under the Fourth Amendment — subject only to a few specifically established and well-delineated exceptions.” Davis v. State, 262 Ga. 578, 422 S.E.2d 546 (1992) citing Katz v. United States, 389 U. S. 347, 357 (88 SC 507, 19 LE2d 576) (1967); see also Gary v. State, 262 Ga. 573 (422 SE2d 426) (1992). The only exceptions would be exigent circumstances, like risk of injury or death or destruction of evidence. State v. David, 269 Ga. 533,501 S.E.2d 494 (1998).

In Clare v. State 135 Ga. App. 281 (1975), the Georgia Court of Appeals held that, “The odor of marijuana smoke is not, in and of itself, sufficient to afford probable cause for a warrantless search, but it may be considered and may be a part of a totality of circumstances sufficient to validate one, [citation], wherein the court held that while “odors alone do not authorize a search without warrant,” a “sufficiently distinctive” odor recognized by one “qualified to know the odor” may form a proper basis for the issuance of a search warrant. In the absence of any other circumstances tending to show the presence of marijuana, the officer’s statements reveal only a suspicion that drugs were being used, which is insufficient to constitute probable cause. Even after an arrest, police may only search your immediate vicinity and not your entire home. In Chimel v. California, 395 U. S. 752 (1969), during an arrest that occurred in the defendant’s home, the court approved a search of the accused’s person and his immediate vicinity but not of his entire home.

To summarize, the protections of the Fourth Amendment are triggered in some degree every single time you interact with a police officer. The longer you’re answering questions in the presence of a police officer, the more likely your encounter has escalated beyond the first tier. You don’t have to answer the door or answer questions; you have a right to ask to be left alone. Remember, it is best to assert your right in a polite and respectful manner. Many officers will push the boundaries up to the point you give them a reason to back off. We hope this information has been helpful. Should you have any further questions regarding your Fourth Amendment rights, don’t hesitate to call (404) 333-0706 or email [email protected].