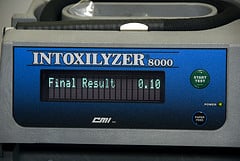

For one, all DUI suspects have to consent to state-administered testing, and giving blood is far more invasive than blowing into a breathalyzer. More suspects may end up refusing a blood test where they would have taken a breath test. Also, there is the problem of alcohol dissipation in the bloodstream, an issue currently being argued in the U.S. Supreme Court case Missouri v. McNeely. Depending on the location of hospitals in comparison to detention centers, as well as hospital wait times, a DUI suspect may wait hours before taking a blood test, which could result in a blood-alcohol level below the legal limit. But despite the evidentiary gap left by the ban on Intoxilyzer testing, prosecutors and police could stress other aspects of DUI prosecution.

Like Georgia’s DUI less safe statute, in Pennsylvania, a DUI suspect can be convicted without a blood or breath test result if it can be proved that they are “generally impaired.” To counteract the restrictions brought on by being forced to obtain blood tests, police may be more stringent in their use of field sobriety tests in an attempt to prove “general impairment.” There is also the reverse Carter defense in which prosecutors could try to prove that a suspect’s blood-alcohol level was above the legal limit at the time of driving and dissipated to a legal level before a blood test could be taken. But if this defense was accepted in court it would open the door to the original Carter defense, which involves questioning the accuracy of blood-alcohol tests by trying to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the amount of alcohol a suspect ingested could not have resulted in an over-the-limit blood-alcohol test. All in all, the questions as to the Intoxilyzer breath testing machines in Pennsylvania, and across the country, are welcome and needed challenges regarding the current standards of prosecution of DUI cases in the U.S.